Does Modern Roasting Have It All Wrong?

How a trip to San Diego caused me to rethink everything.

There are two schools in the roasting world. One obsesses over data. The other swears by feel. As with most matchups, time favors tech—and that’s a good thing. Few long for a return to anesthesia-free dental work. In the coffee world, that’s meant a push toward data.

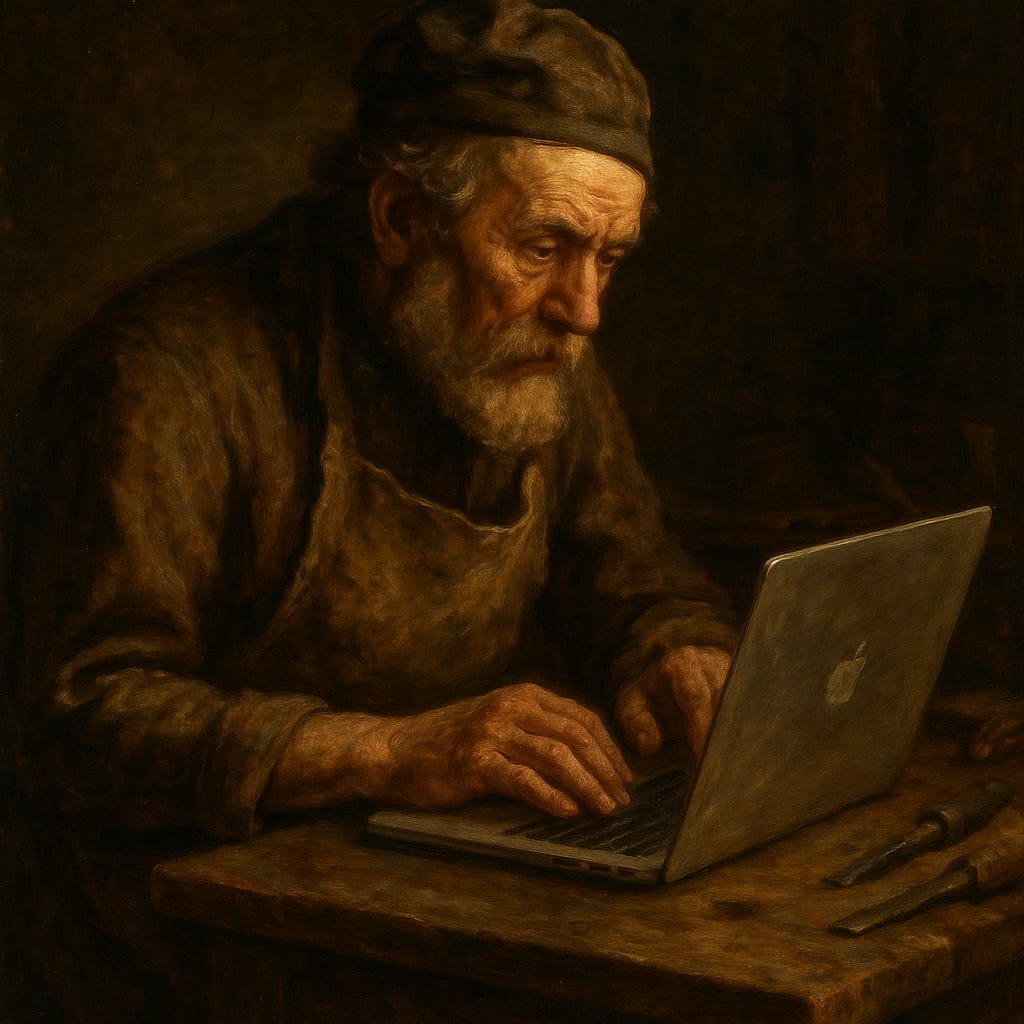

Gone are the days of bespectacled craftsmen hovering over triers, using quill and parchment to mark time and temp. Today’s roasters glue themselves to laptops, staring at data and roast curves. The approach packs all the romance of a Papa Roach tune, but it works. And its efficacy has led to a good deal of eye-rolling toward the dinosaurs who still sit there sniffing beans mid-roast, as though flaring nostrils can match the precision of finely tuned thermocouples.

Until recently, I was a practiced eye-roller. Last week, however, I had a mystifying experience. It happened in San Diego—which is mystifying in its own way—and it spun my thinking about old world versus newfangled.

There’s a guy named Chuck Patton. You may know him, or at least you may know his company: Bird Rock. It’s one of the OG specialty roasters, an outfit Chuck founded in the early 2000s and rode to prominence before selling it and moving on to greener pastures*. His time in the coffee world was marked by extraordinary achievement. He won Roaster of the Year from Roast magazine. His coffees have received gargantuan scores and landed on Coffee Review’s annual Top 30 list multiple times. People magazine thrice declared him Sexiest Roaster Alive—not the most competitive category, but sexy has no time for relativism.

I met Chuck because I tried a Yemeni coffee of his, and it kind of blew my mind. The MFC customers among you will know I roast Yemeni lots quite a bit. What you may not know is that beans from Yemen are a bitch to get right. They seem to have a mind of their own, reacting to gas and airflow adjustments with the erraticism of a U.S. commander-in-chief. Chuck’s Yemen was a thing to behold—spiced, lemony, rich and resonant, with a knockout note of candied citrus. It was so good that I reached out to Chuck and made plans to drive to San Diego to roast with him.

I found Chuck in a very cool shop called Coffee Cycle**. He was parked behind a Giesen—a thundering block of steel with a sapphire burner and a double-walled drum. We shook hands (behold my mastery of needless detail). I brought a bunch of coffee, including an Ethiopian natural. He measured a batch, and we dropped it into the Giesen. That’s when things got surprising.

Chuck opened his laptop, and I squinted at the screen—where was Rate of Rise?

If you don’t roast, this won’t mean much, but just know that Rate of Rise is the most obsessed-over piece of data in the roasting world. Modern wisdom says it can tell you how a coffee is going to taste before you even brew it.

Yet Chuck wasn’t tracking it.

When I asked him why, he shrugged. Data is useful, he said, but too many roasters obsess over it. If you don’t know the craft, a laptop isn’t going to save you.

Chuck and I roasted for hours, and he executed each batch by feel. Sure, he used his laptop, minding bean temp and time, but he didn’t stare at curves. From my perspective, it was so old school, he may as well have been timing each roast with a cuckoo clock and measuring heat by holding his palm over the burner. He used the trier over and over, sniffing the beans, gauging their roast stage, letting aroma guide his adjustments. He instructed me to do the same. When it came time to drop the batch, Chuck did so by color alone.

Three days later, I cupped the coffees. My reaction was laughter.

The stuff was comically good. Fruity as a farmers market. Rich as an oligarch. Refined as a bespoke suit. I gave some to my wife and brother. They reacted similarly (this isn’t true; I’m the only maniac who laughed). The coffee was so good, it caused me to rethink everything I believed about old-school roast technique.

Could it be that we’ve gotten it wrong? Might advancements in data have caused us to overlook the very real advantages of old-world styles? Have we, in other words, mistaken technology for wisdom?

I spoke with my therapist about this. He advised me to write an article—I paid him handsomely for that advice—so I sat down and started penning everything you’ve just read to get my thoughts straight. Here’s where I’ve landed:

I learned to roast using data. And I love data. I find tracking curves genuinely enjoyable, and I can discern flavor differences in their trajectories. Also—at the risk of sounding immodest—I can roast world-class stuff. So there’s no denying the advantages of modern approaches.

But if my laptop crashes, I want to be able to fly without instruments. I want my senses so finely tuned that a simple flare of the nostrils matches the precision of a thermocouple. I want to drop by color, time by cuckoo clock, and measure heat by shoving the palm of my hand over the burner. I want to do these things not just because I long for something more romantic than your average Papa Roach tune, but because… they work.

Chuck proved that.

So maybe the best version of roasting is a hybrid: old world and newfangled. Ancient technique and modern instruments. That’s the direction I aim to go.

I suspect I’ll need to make a few more stops in San Diego along the way.

If you want to throw in on the debate between old world and new school, do so below. I’d love to hear from you.

And if you want to try some of Chuck’s coffee, he sells limited bags here. If you’re an aspiring roaster, you can also contact him for training and consultations.

*Chuck no longer roasts for Bird Rock. Don’t buy their bags expecting it to come from him.

**The San Diegans among you should visit this place.

I love your writing style and humor. Perhaps you could paste your prose on your bags of coffee.

Data does a few things. 1) It can dramatically raise the average quality of all roasting. 2) it increases reliability and fine-tuning. But it doesn't always have a way to generate creativity. Sometimes "mistakes" are sources of innovation. It's good to have a way to change directions (which will then be quantified and refined).